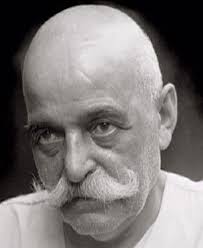

Although in the past few years various recordings of the music of G. I. Gurdjieff have been issued and are generally available, it may still surprise many who are aware of the Armenian-Greek teacher to learn that he was, in fact, the composer of an impressive number of musical works, mainly for the piano.

Gurdjieff’s master-pupil relationship with the Russian composer Thomas de Hartmann has

been affectionately chronicled by de Hartmann and his wife, Olga, but the unusual and surely unique musical collaboration between the two men still remains an uncanny phenomenon, producing a result which would have been patently impossible for either one of them alone.

The sheer volume of work that emerged from this joining of forces attests to the importance which Gurdjieff seems to have attached to music as an element of his teaching, perhaps even as a repository of precise knowledge. His cosmological ideas make extensive use of the language of musical structure and function.

While the earliest and crucially important phase of their collaboration was involved with music for the sacred dances—or Movements, a vital component of Gurdjieff’s method—the compositions included in a recently released four-record album, performed by de Hartmann himself, are not related to the Movements, but are pieces of absolute music, albeit with richly evocative titles. These recordings, made in the 1950s under somewhat casual conditions and with amateur tape equipment, sometimes even without de Hartmann’s knowledge, have now been reengineered with the most advanced techniques. Considering the modesty of the original effort, the results are remarkably good. What we have is a clean, quiet recording of performances which, without a doubt, set the standard for the interpretation of these deceptively simple pieces. As a pianist, de Hartmann was not only a superb technician, but played with great depth of understanding and poetic sensibility; and then, of course, it was his own music. Unlike, therefore, any other recording of these works, this one gives the sense of the pianist-composer going to the very heart of each phrase. The music emerges in all clarity and integrity; the pianist and his personality disappear entirely from the scene. One cannot ask more from any musical rendering.

The greater part of these works was composed from 1924 through 1926 at Gurdjieff’s Institute in Fontainebleau, near Paris. Many of the compositions bear specific dates which indicate periods of a literally daily musical output and suggest the great intensity of the collaborative-creative process, often for weeks at a stretch.

The compositions which comprise the present album have been well chosen, offering a broad view of various aspects of the Gurdjieff / de Hartmann work. There are hymns of a solemn or contemplative nature, quite unlike our usual idea of that form, often drawing from the idiom of the Russian Orthodox liturgy, or else echoing music Gurdjieff remembered hearing in remote Asian temples and monasteries. At the other end of the spectrum are the ingenuous dancelike evocations of simple, ethnic folk melodies. And in between are suggestions of the Near-Eastern improvisation known as the taksim; subjective songs of intimate, personal expression in the music of the Sayyids, proverbial descendants of Mohammed; melodies of great warmth and humanity rather more in the Western harmonic style, such as the Bokharian Dervish, and Rejoice, Beelzebub; and, also, excerpts from the score of Gurdjieff’s unproduced ballet, The Struggle of the Magicians.

Describing the external forms and styles of this music does not, however, help to illuminate its inner essence, which remains strangely enigmatic. What is the source of its compelling force, its ineffable atmosphere, its capacity to cast a spell on the listener while bringing him more intensely into contact with himself?

To begin with, the genesis of these pieces, the method of their composition, is singular, to say the least. De Hartmann has engagingly adumbrated the process, in which Gurdjieff, who could improvise movingly on the harmonium but was in no way a trained composer, would whistle or pick out with one finger on the piano some characteristically Near-Eastern phrase. This and other melodic fragments were somehow assembled and shaped by de Hartmann under Gurdjieff’s watchful eye. Harmonies would attach themselves, rhythmic patterns would add momentum, gradually a form would appear. Yet despite de Hartmann’s schooled and polished compositional mastery, the influence of Gurdjieff on this “fleshing-out” process seems unquestionable. De Hartmann’s own personal style in his numerous orchestral, chamber, and operatic works reflects the transition from an elegant and charming Russian-French neoromanticism into an early 20th-century modernism, peculiarly related to the contemporary cubist and expressionist schools of painting, with an almost naive use of dissonant tone-clusters, a tendency toward mechanistic rhythms, a taste for ironic or sarcastic harmonic configurations.

With very rare exceptions, none of this appears in the music de Hartmann created with Gurdjieff. Occasional dissonances are transformed into something subtle and mysterious; the entire musical stance is a different one. These works seem, in fact, almost devoid of any device designed for effect. They are characterized rather by a directness of feeling and simplicity of structure, even when the ultimate “meaning” is more recondite. The melodies are often oriental in idiom, occasionally even verging on the trite. The harmonic underpinning (a Western adaptation, nonexistent in Eastern music) is mostly triadic or made of fourths or fifths, or else uses the familiar organ-point or drone. When the harmony is on occasion more complex (de Hartmann’s touch, to be sure) it is rarely with intent to weave elaborate chordal progressions, but rather to make more emphatic, pungent, or poignant, some melodic movement. The rhythms are often almost primitively straightforward. One might say this music, whether it is being lyrically introspective, dancelike or prayerful, always feels stripped down, its bones showing. Textures are of minimal interest, embellishments only for the intensification of expression.

On the other hand, in rare instances, the music may seem, for a moment, awkward, ungainly, taking an incomprehensible turn for no apparent reason, as though some subtle intention is eluding us. What feels at first like a mistake leaves us later not so sure. Has de Hartmann deliberately allowed a touch of Gurdjieff’s amateurism to remain “uncorrected?” Or, finally, is it absurd to apply here the ordinary academic principles of musical procedure? Is Gurdjieff eschewing also, as he did with the “literary,” the “bon ton musical language?”

But leaving aside these relatively subtle points, one might guess that the trained listener will very possibly, on first hearing, instantly dismiss this music as typically folkloristic, indigenous to the ethnic and religious crossroads where Gurdjieff was born and spent his early years, and as a characteristic example of the incorporation of such source material into concert works, so common among Russian composers of this period, for whom this style seemed attractively exotic.

But a deeper contact with the Gurdjieff music will quickly show the error in likening it either to traditional folk or religious music itself or to any trivial popularization of it. The similarity is principally one of vocabulary, all on the surface. Gurdjieff obviously used it because it was quite simply the language he knew, and, as it happens, a language rich in a kind of natural, universal, human expression. But his purpose in music went much deeper.

In Gurdjieff’s view, most art we know is subjective, both in its creation and its reception. He saw objective art—much rarer—as having a specific relationship to the properties of feeling, as emanating precise vibrations which influence the feelings directly, organically, predictably. Objective art, he said, affects all people in the same way.

Unavoidably we are drawn to ask: Is Gurdjieff’s music an example of objective art? Of course it is impossible to say. His various works are clearly on different levels. And yet one may well wonder, for example, when hearing the last composition in this series of records, entitled “Remembrance.” Here is the archetype of the essential Gurdjieffian “sound.” Anything that could evoke sentiment, nostalgia, charm, or sadness, is nowhere to be found. The music is naked, unadorned, and yet not stark or severe. Instead, a profound searching tone follows the questioning single line, an angular, unpredictable melody that seems to find no resting place, hesitating, feeling its way from moment to moment, supported by a three-voiced harmonic base, likewise elusive, curiously unwilling to resolve itself. And all haunted by a deep, indescribable feeling, as though gazing intently inward, without comment. Objective.

To compare this music with other, more familiar, kinds of music, classic or otherwise, is pointless. Although its materials are utterly simple, recognizable, even conventional, it defies classification. It seems to have been created with a special aim, a special intent. It is, finally sui generis. It makes statements and asks questions not to be found elsewhere.

~ • ~

[Laurence Rosenthal is a composer and pianist. His symphonic works have been performed by such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic and under conductors such as Leonard Bernstein and Erich Leinsdorf. He adapted the Gurdjieff / de Hartmann music to the film Meetings with Remarkable Men and has composed the scores for many television miniseries including Mussolini, Peter the Great, Anastasia, The Bourne Identity, and George Lucas’ Young Indiana Jones. Mr. Rosenthal has won 7 Emmys.—G.I.R. Eds.]

Copyright © 1985 Laurence Rosenthal

This webpage © 1999 Gurdjieff Electronic Publishing

Featured: Summer 1999 Issue, Vol. II (4)

Revision: July 1, 1999 |